June 22, 2023

The Story Behind Last Week's Let's Encrypt Downtime

Last Thursday (June 15th, 2023), Let's Encrypt went down for about an hour, during which time it was not possible to obtain certificates from Let's Encrypt. Immediately prior to the outage, Let's Encrypt issued 645 certificates which did not work in Chrome or Safari. In this post, I'm going to explain what went wrong and how I detected it.

The Law of Precertificates

Before I can explain the incident, we need to talk about Certificate Transparency. Certificate Transparency (CT) is a system for putting certificates issued by publicly-trusted CAs, such as Let's Encrypt, in public, append-only logs. Certificate authorities have a tremendous amount of power, and if they misuse their power by issuing certificates that they shouldn't, traffic to HTTPS websites could be intercepted by attackers. Historically, CAs have not used their power well, and Certificate Transparency is an effort to fix that by letting anyone examine the certificates that CAs issue.

A key concept in Certificate Transparency is the "precertificate". Before issuing a certificate, the certificate authority creates a precertificate, which contains all of the information that will be in the certificate, plus a "poison extension" that prevents the precertificate from being used like a real certificate. The CA submits the precertificate to multiple Certificate Transparency logs. Each log returns a Signed Certificate Timestamp (SCT), which is a signed statement acknowledging receipt of the precertificate and promising to publish the precertificate in the log for anyone to download. The CA takes all of the SCTs and embeds them in the certificate. When a CT-enforcing browser (like Chrome or Safari) validates the certificate, it makes sure that the certificate embeds a sufficient number of SCTs from trustworthy logs. This doesn't prevent the browser from accepting a malicious certificate, but it does ensure that the precertificate is in public logs, allowing the attack to be detected and action taken against the CA.

The certificate itself may or may not end up in CT logs. Some CAs, notably Let's Encrypt and Sectigo, automatically submit their certificates. Certificates from other CAs only end up in logs if someone else finds and submits them. Since only the precertificate is guaranteed to be logged, it is essential that a precertificate be treated as incontrovertible proof that a certificate containing the same data exists. When someone finds a precertificate for a malicious or non-compliant certificate, the CA can't be allowed to evade responsibility by saying "just kidding, we never actually issued the real certificate" (and boy, have they tried). Otherwise, CT would be useless.

There are two ways a CA could create a certificate. They could take the precertificate, remove the poison extension, add the SCTs, and re-sign it. Or, they could create the certificate from scratch, making sure to add the same data, in the same order, as used in the precertificate.

The first way is robust because it's guaranteed to produce a certificate which matches the precertificate. At least one CA, Sectigo, uses this approach. Let's Encrypt uses the second approach. You can probably see where this is going...

The Let's Encrypt incident

On June 15, 2023, Let's Encrypt deployed a planned change to their certificate configuration which altered the contents of the Certificate Policies extension from:

X509v3 Certificate Policies:

Policy: 2.23.140.1.2.1

Policy: 1.3.6.1.4.1.44947.1.1.1

CPS: http://cps.letsencrypt.org

to:

X509v3 Certificate Policies:

Policy: 2.23.140.1.2.1

Unfortunately, any certificate which was requested while the change was being rolled out could have its precertificate and certificate created with different configurations. For example, when Let's Encrypt issued the certificate with serial number 03:e2:26:7b:78:6b:7e:33:83:17:dd:d6:2e:76:4f:cb:3c:71, the precertificate contained the new Certificate Policies extension, and the certificate contained the old Certificate Policies extension.

This had two consequences:

First, this certificate won't work in Chrome or Safari, because its SCTs are for a precertificate containing different data from the certificate. Specifically, the SCTs fail signature validation. When logs sign SCTs, they compute the signature over the data in the precertificate, and when browsers verify SCTs, they compute the signature over the data in the certificate. In this case, that data was not the same.

Second, remember how I said that precertificates are treated as incontrovertible proof that a certificate containing the same data exists? When Let's Encrypt issued a precertificate with the new Certificate Policies value, it implied that they also issued a certificate with the new Certificate Policies value. Thus, according to the Law of Precertificates, Let's Encrypt issued two certificates with serial number 03:e2:26:7b:78:6b:7e:33:83:17:dd:d6:2e:76:4f:cb:3c:71:

- A certificate containing the old Certificate Policies extension

- A certificate containing the new Certificate Policies extension (implied by the existence of the precertificate with the new Certificate Policies extension)

Issuing two certificates with the same serial number is a violation of the Baseline Requirements for the Issuance and Management of Publicly-Trusted Certificates. Consequentially, Let's Encrypt must revoke the certificate and post a public incident report, which must be noted on their next audit statement.

You might think that it's harsh to treat this as a compliance incident if Let's Encrypt didn't really issue two certificates with the same serial number. Unfortunately, they have no way of proving this, and the whole reason for Certificate Transparency is so we don't have to take CAs at their word that they aren't issuing certificates that they shouldn't. Any exception to the Law of Precertificates creates an opening for a malicious CA to exploit.

How I found this

My company, SSLMate, operates a Certificate Transparency monitor called Cert Spotter, which continuously downloads and indexes the contents of every Certificate Transparency log. You can use Cert Spotter to get notifications when a certificate is issued for one of your domains, or search the database using a JSON API.

When Cert Spotter ingests a certificate containing embedded SCTs, it verifies each SCT's signature and audits that the log really published the precertificate. (If it detects that a log has broken its promise to publish a precertificate, I'll publicly disclose the SCT and the log will be distrusted. Happily, Cert Spotter has never found a bogus SCT, though it has detected logs violating other requirements.)

On Thursday, June 15, 2023 at 15:41 UTC, Cert Spotter began sending me alerts about certificates containing embedded SCTs with invalid signatures. Since I was getting hundreds of alerts, I decided to stop what I was doing and investigate.

I had received these alerts several times before, and have gotten pretty good at zeroing in on the problem. When only one SCT in a certificate has an invalid signature, it probably means that the CT log screwed up. When all of the embedded SCTs have an invalid signature, it probably means the CA screwed up. The most common reason is issuing certificates that don't match the precertificate. So I took one of the affected certificates and searched for precertificates containing the same serial number in Cert Spotter's database of every (pre)certificate ever logged to Certificate Transparency. Decoding the certificate and precertificate with the openssl command immediately revealed the different Certificate Policies extension.

Since I was continuing to get alerts from Cert Spotter about invalid SCT signatures, I quickly fired off an email to Let's Encrypt's problem reporting address alerting them to the problem.

I sent the email at 15:52 UTC. At 16:08, Let's Encrypt replied that they had paused issuance to investigate. Meanwhile, I filed a CA Certificate Compliance bug in Bugzilla, which is where Mozilla and Chrome track compliance incidents by publicly-trusted certificate authorities.

At 16:54, Let's Encrypt resumed issuance after confirming that they would not issue any more certificates with mismatched precertificates.

On Friday, June 16, 2023, Let's Encrypt emailed the subscribers of the affected certificates to inform them of the need to replace their certificates.

On Monday, June 19, 2023 at 18:00 UTC, Let's Encrypt revoked the 645 affected certificates, as required by the Baseline Requirements. This will cause the certificates to stop working in any client that checks revocation, but remember that these certificates were already being rejected by Chrome and Safari for having invalid SCTs.

On Tuesday, June 20, 2023, Let's Encrypt posted their public incident report, which explained the root cause of the incident and what they're doing to prevent it from happening again. Specifically, they plan to add a pre-issuance check that ensures certificates contain the same data as the precertificate.

Hundreds of websites are still serving broken certificates

I've been periodically checking port 443 of every DNS name in the affected certificates, and as of publication time, 261 certificates are still in use, despite not working in CT-enforcing or revocation-checking clients.

I find it alarming that a week after the incident, 40% of the affected certificates are still in use, despite being rejected by the most popular browsers and despite affected subscribers being emailed by Let's Encrypt. I thought that maybe these certificates were being used by API endpoints which are accessed by non-browser clients that don't enforce CT or check revocation, but this doesn't appear to be the case, as most of the DNS names are for bare domains or www subdomains. It's fortunate that Let's Encrypt issued only a small number of non-compliant certificates, because otherwise it would have broken a lot of websites.

There is a new standard under development called ACME Renewal Information which enables certificate authorities to inform ACME clients to renew certificates ahead of their normal expiration. Let's Encrypt supports ARI, and used it in this incident to trigger early renewal of the affected certificates. Clearly, more ACME clients need to add support for ARI.

This is my 50th CA compliance bug

It turns out this is the 50th CA compliance bug that I've filed in Bugzilla, and the 5th which was uncovered by Cert Spotter's SCT signature checks. Additionally, I reported a number of incidents before 2018 which didn't end up in Bugzilla.

Some of the problems I uncovered were quite serious (like issuing certificates without doing domain validation) and snowballed until the CA was ultimately distrusted. Most are minor in comparison, and ten years ago, no one would have cared about them: there was no Certificate Transparency to unearth non-compliant certificates, and even when someone did notice, the revocation requirement was not enforced, and CAs were not required to file incident reports or document the non-compliance on their next audit. Thankfully, that's no longer the case, and even compliance violations that seem minor are treated seriously, which has led to enormous improvements in the certificate ecosystem:

- The improvements which certificate authorities make in response to seemingly-minor incidents also improve their compliance with the most security-critical rules.

- TLS clients no longer need to work around non-standards-compliant certificates, which means they can be simpler. Simpler code is easier to make secure.

- The way that CAs handle minor incidents can uncover much larger problems. Minor compliance problems are like "Brown M&M's".

Mozilla deserves enormous credit for being the first to require public incident reports from CAs, as does Google for creating and fostering Certificate Transparency.

You should monitor Certificate Transparency too

One limitation of my compliance monitoring is that I am generally only able to detect certificates that are intrinsically non-compliant, like those which violate encoding rules or are valid for too many days. While I do monitor certificates for domains that are likely to be abused, like example.com and test.com, I can't tell if a certificate issued for your domain is authorized or not. Only you know that.

Fortunately, it's pretty easy to monitor Certificate Transparency and get alerts when a certificate is issued for one of your domains. Cert Spotter has a standalone, open source version that's easy to set up. The paid version has additional features like expiration monitoring, Slack integration, and ways to filter alerts so you're not bothered about legitimate certificates. But most importantly, subscribing to the paid version helps me continue my compliance monitoring of the certificate authority ecosystem.

June 18, 2023

The Difference Between Root Certificate Authorities, Intermediates, and Resellers

It happens every so often: some organization that sells publicly-trusted SSL certificates does something monumentally stupid, like generating, storing, and then intentionally disclosing all of their customers' private keys (Trustico), letting private keys be stolen via XSS (ZeroSSL), or most recently, literally exploiting remote code execution in ACME clients as part of their issuance process (HiCA aka QuantumCA).

When this happens, people inevitably refer to the certificate provider as a certificate authority (CA), which is an organization with the power to issue trusted certificates for any domain name. They fear that the integrity of the Internet's certificate authority system has been compromised by the "CA"'s incompetence. Something must be done!

But none of the organizations listed above are CAs - they just take certificate requests and forward them to real CAs, who validate the request and issue the certificate. The Internet is safe - from these organizations, at least.

In this post, I'm going to define terms like certificate authority, root CA, intermediate CA, and reseller, and explain whom you do and do not need to worry about.

Note that I'm going to talk only about publicly-trusted SSL certificate authorities - i.e those which are trusted by mainstream web browsers.

Certificate Authority Certificates

"Certificate authority" is a label that can apply both to SSL certificates and to organizations. A certificate is a CA if it can be used to issue certificates which will be accepted by browsers. There are two types of CA certificates: root and intermediate.

Root CA certificates, also known as "trust anchors" or just "roots", are shipped with your browser. If you poke around your browser's settings, you can find a list of root CA certificates.

Intermediate CA certificates, also known as "subordinate CAs" or just "intermediates", are certificates with the "CA" boolean set to true in the Basic Constraints extension, and which were issued by a root or another intermediate. If you decode an intermediate CA certificate with openssl, you'll see this in the extensions section:

X509v3 Basic Constraints: critical

CA:TRUE

When you connect to a website, your browser has to verify that the website's certificate was issued by a CA certificate. If the website's certificate was issued by a root, it's easy because the browser already knows the public key needed to verify the certificate's signature. If the website's certificate was issued by an intermediate, the browser has to retrieve the intermediate from elsewhere, and then verify that the intermediate was issued by a CA certificate, recurring as necessary until it reaches a root. The web server can help the browser out by sending intermediate certificates along with the website's certificate, and some browsers are able to retrieve intermediates from the URL included in the certificate's AIA (Authority Information Access) field.

The purpose of this post is to discuss organizations, so for the rest of this post, when I say "certificate authority" or "CA" I am referring to an organization, not a certificate, unless otherwise specified.

Certificate Authority Organizations

An organization is a certificate authority if and only if they hold the private key for one or more certificate authority certificates. Holding the private key for a CA certificate is a big deal because it gives the organization the power to create certificates that are valid for any domain name on the Internet. These are essentially the Keys to the Internet.

Unfortunately, figuring out who holds a CA certificate's private key is not straightforward. CA certificates contain an organization name in their subject field, and many people reasonably assume that this must be the organization which holds the private key. But as I explained earlier this year, this is often not the case. I spend a lot of time researching the certificate ecosystem, and I am not exaggerating when I say that I completely ignore the organization name in CA certificates. It is useless. You have to look at other sources, like audit statements and the CCADB, to figure out who really holds a CA certificate's key. Consequentially, just because you see a company's name in a CA certificate, it does not mean that it has a key which can be used to create certificates.

Internal vs External Intermediate Certificates

CAs aren't allowed to issue website certificates directly from root certificates, so any CA which operates a root certificate is going to have to issue themselves at least one intermediate certificate. Since the CA retains control of the private key for the intermediate, these are called internally-operated intermediate certificates. Most intermediate certificates are internally-operated.

CAs are also able to issue intermediate certificates whose private key is held by another organization, making the other organization a certificate authority too. These are called externally-operated intermediate certificates, and there are two reasons they exist.

The more legitimate reason is that the other organization operates, or intends to operate, root certificates, and would like to issue certificates which work in older browsers whose trust stores don't include their roots. By getting an intermediate from a more-established CA, they can issue certificates which chain back to a root that is in more trust stores. This is called cross-signing, and a well-known example is Identrust cross-signing Let's Encrypt.

The less-savory reason is that the other organization would like to become a certificate authority without having to go through the onerous process of asking each browser to include them. Historically, this was a huge loophole which allowed organizations to become CAs with less oversight and thus less investment into security and compliance. Thankfully, this loophole is closing, and nowadays Mozilla and Chrome require CAs to obtain approval before issuing externally-operated intermediates to organizations which aren't already trusted CAs. I would not be surprised if browsers eventually banned the practice outright, leaving cross-signing as the only acceptable use case for externally-operated intermediates.

Certificate Resellers

There's no standard definition of certificate reseller, but I define it as any organization which provides certificates which they do not issue themselves. When someone requests a certificate from a reseller, the reseller forwards the request to a certificate authority, which validates the request and issues the certificate. The reseller has no access to the CA certificate's private key and no ability to cause issuance themselves. Typically, the reseller will use an API (ACME or proprietary) to request certificates from the CA. My company, SSLMate, is a reseller (though these days we mostly focus on Certificate Transparency monitoring).

The relationship between the reseller and the CA can take many forms. In some cases, the reseller may enter into an explicit reseller agreement with the CA and get access to special pricing or reseller-only APIs. In other cases, the reseller might obtain certificates from the CA using the same API and pricing available to the general public. The reseller might not even pay the CA - there's nothing stopping someone from acting like a reseller for free CAs like Let's Encrypt. For example, DNSimple provides paid certificates issued by Sectigo right alongside free certificates issued by Let's Encrypt. The CA might not know that their certificates are being resold - Let's Encrypt, for instance, allows anyone to create an anonymous account.

An organization may be a reseller of multiple CAs, or even be both a reseller and a CA. A reseller might not get certificates directly from a CA, but via a different reseller (SSLMate did this in the early days because it was the only way to get good pricing without making large purchase commitments).

A reseller might just provide certificates to customers, or they might use the certificates to provide a larger service, such as web hosting or a CDN (for example, Cloudflare).

White-Label / Branded Intermediate Certificates

Ideally, it would be easy to distinguish a reseller from a CA. However, most resellers are middlemen who provide no value over getting a certificate directly from a CA, and they don't want people to know this. So, for the right price, a CA will issue themselves an internally-operated intermediate CA certificate with the reseller's name in the organization field, and when the reseller requests a certificate, the CA will issue the certificate from the "branded" intermediate certificate instead of from an intermediate certificate with the CA's name in it.

The reseller does not have access to the private key of the branded intermediate certificate. Except for the name, everything about the branded intermediate certificate - like the security controls and the validation process - is exactly the same as the CA's non-branded intermediates. Thus, the mere existence of a branded intermediate certificate does not in any way affect the integrity of the certificate authority ecosystem, regardless of how untrustworthy, incompetent, or malicious the organization named in the certificate is.

What Should Worry You?

I spend a lot of time worrying about bad certificate authorities, but bad resellers don't concern me. A bad reseller can harm only their own customers, but a bad certificate authority can harm the entire Internet. Yeah, it sucks if you choose a reseller who screws you, but it's no different from choosing a bad hosting provider, domain registrar, or any of the myriad other vendors needed to host a website. As always, caveat emptor. In contrast, you can pick the best, most trustworthy certificate authority around, and some garbage CA you've never heard of can still issue an attacker a certificate for your domain. This is why web browsers tightly regulate CAs, but not resellers.

Unfortunately, this doesn't stop people from freaking out when a two-bit reseller with a branded intermediate (such as Trustico, ZeroSSL, or HiCA/QuantumCA) does something awful. People flood the mozilla-dev-security-policy mailing list to voice their concerns, including those who have little knowledge of certificates and have never posted there before. These discussions are a distraction from far more important issues. While the HiCA discussion was devolving into off-topic blather, the certificate authority Buypass disclosed in an incident report that they have a domain validation process which involves their employees manually looking up and interpreting CAA records. They are far from the only CA which does domain validation manually despite it being easy to automate, and it's troubling because having a human involved gives attackers an opening to exploit mistakes, bribery, or coercion to get unauthorized certificates for any domain. Buypass' incident response, which blames "human error" instead of addressing the root cause, won't make headlines on Hacker News or be shared on Twitter with the popcorn emoji, but it's actually far more concerning than the worst comments a reseller has ever made.

About the Author

I've reported over 50 certificate authority compliance issues, and uncovered evidence that led to the distrust of multiple certificate authorities and Certificate Transparency logs. My research has prompted changes to ACME and Mozilla's Root Store Policy. My company, SSLMate, offers a JSON API for searching Certificate Transparency logs and Cert Spotter, a service to monitor your domains for unauthorized, expiring, or incorrectly-installed certificates.

If you liked this post, you might like:

- The SSL Certificate Issuer Field is a Lie

- The Difference Between Domain Registries and Registrars

- Checking if a Certificate is Revoked: How Hard Can It Be?

Stay Tuned: Let's Encrypt Incident

By popular demand, I will be blogging about how I found the compliance bug which prompted last week's Let's Encrypt downtime. Be sure to subscribe by email or RSS, or follow me on Mastodon or Twitter.

January 18, 2023

The SSL Certificate Issuer Field is a Lie

A surprisingly hard, and widely misunderstood, problem with SSL certificates is figuring out what organization (called a certificate authority, or CA) issued a certificate. This information is useful for several reasons:

- You've discovered an unauthorized certificate for your domain via Certificate Transparency logs and need to contact the certificate authority to get the certificate revoked.

- You've discovered a certificate via Certificate Transparency and want to know if it was issued by one of your authorized certificate providers.

- You're a researcher studying the certificate ecosystem and want to count how many certificates each certificate authority has issued.

On the surface, this looks easy: every certificate contains an issuer field with human-readable attributes, including an organization name. Problem solved, right?

Not so fast: a certificate's issuer field is frequently a lie that tells you nothing about the organization that really issued the certificate. Just look at the certificate chain currently served by doordash.com:

According to this, DoorDash's certificate was issued by an intermediate certificate belonging to "Cloudflare, Inc.", which was issued by a root certificate belonging to "Baltimore". Except Cloudflare is not a certificate authority, and Baltimore is a city.

In reality, both DoorDash's certificate and the intermediate certificate were issued by DigiCert, a name which is mentioned nowhere in the above chain. What's going on?

First, Cloudflare has paid DigiCert to create and operate an intermediate certificate with Cloudflare's name in it. DigiCert, not Cloudflare, controls the private key and performs the security-critical validation steps prior to issuance. All Cloudflare does is make an API call to DigiCert. Certificates issued from the "Cloudflare" intermediate are functionally no different from certificates issued from any of DigiCert's other intermediates. This type of white-labeling is common in the certificate industry, since it lets companies appear to be CAs without the expense of operating a CA.

Sidebar: that time everyone freaked out about Blue Coat

In 2016 Symantec created an intermediate certificate with "Blue Coat" in the organization name. This alarmed many non-experts who thought Blue Coat, a notorious maker of TLS interception devices, was now operating a certificate authority. In reality, it was just a white-label Symantec intermediate certificate, operated by Symantec under their normal audits with their normal validation procedures, and it posed no more risk to the Internet than any of the other intermediate certificates operated by Symantec.

What about "Baltimore"? That's short for Baltimore Technologies, a now-defunct infosec company, who acquired GTE's certificate authority subsidiary (named CyberTrust) in 2000, which they then sold to a company named Betrusted in 2003, which merged with TruSecure in 2004, who rebranded back to CyberTrust, which was then acquired by Verizon in 2007, who then sold the private keys for their root certificates to DigiCert in 2015. So "Baltimore" hasn't been accurate since 2003, and the true owner has changed four times since then.

Mergers and acquisitions are common in the certificate industry, and since the issuer name is baked into certificates, the old name can persist long after a different organization takes over. Even once old certificates expire, the acquiring CA might keep using the old name for branding purposes. Consider Thawte, which despite not existing since 1999, could still be found in new certificates as recently as 2017. (Thawte was sold to Verisign, then Symantec, and then DigiCert, who finally stopped putting "Thawte" in the issuer organization name.)

Consequentially, the certificate issuer field is completely useless for human consumption, and causes constant confusion. People wonder why they get Certificate Transparency alerts for certificates issued by "Cloudflare" when their CAA record has only digicert.com in it. Worse, people have trouble revoking certificates: consider this incident where someone tried to report a compromised private key to the certificate reseller named in the certificate issuer field, who failed to revoke the certificate and then ghosted the reporter. If the compromised key had been reported to the true certificate authority, the CA would have been required to revoke and respond within 24 hours.

I think certificate tools should do a better job helping people understand who issued certificates, so a few years ago I started maintaining a database which maps certificate issuers to their actual organization names. When Cert Spotter sends an alert about an unknown certificate found in Certificate Transparency logs, it shows the name from this database - not the name from the certificate issuer field. It also includes correct contact information for requesting revocation.

As of this month, the same information is available through SSLMate's Certificate Transparency Search API, letting you integrate useful certificate issuer information into your own applications. Here's what the API looks like for the doordash.com certificate (some fields have been truncated for clarity):

{

"id":"3779499808",

"tbs_sha256":"eb3782390d9fb3f3219129212b244cc34958774ba289453a0a584e089d0f2b86",

"cert_sha256":"6e5c90eb2e592f95fabf68afaf7d05c53cbd536eee7ee2057fde63704f3e1ca1",

"dns_names":["*.doordash.com","doordash.com","sni.cloudflaressl.com"],

"pubkey_sha256":"456d8df5c5b1097c775a778d92f50d49b25720f672fcb0b8a75020fc85110bea",

"issuer":{

"friendly_name":"DigiCert",

"website":"https://www.digicert.com/",

"caa_domains":["digicert.com","symantec.com","geotrust.com","rapidssl.com", ...],

"operator":{"name":"DigiCert","website":"https://www.digicert.com/"},

"pubkey_sha256":"144cd5394a78745de02346553d126115b48955747eb9098c1fae7186cd60947e",

"name":"C=US, O=\"Cloudflare, Inc.\", CN=Cloudflare Inc ECC CA-3"

},

"not_before":"2022-05-29T00:00:00Z",

"not_after":"2023-05-29T23:59:59Z",

"revoked":false,

"problem_reporting":"Send email to revoke@digicert.com or visit https://problemreport.digicert.com/"

}

Note the following fields:

- The

friendly_namefield contains "DigiCert", not "Cloudflare". This field is useful for displaying to humans. - The

caa_domainsfield contains the CAA domains used by the CA. You can compare this array against your domain's CAA record set to determine if the certificate is authorized - at least one of the domains in the array should also be in your CAA record set. - The

operatorfield contains details about the company which operates the CA. In this example, the operator name is the same as the friendly name, but later in this post I'll describe an edge case where they are different. - The

problem_reportingfield contains instructions on how to contact the CA to request the certificate be revoked.

The data comes from a few places:

-

The Common CA Database (CCADB)'s

AllCertificateRecordsreport, which is a CSV file listing every intermediate certificate trusted by Apple, Microsoft, or Mozilla. To find out who operates an intermediate certificate, you can look up the fingerprint in the "SHA-256 Fingerprint" column, and then consult the "Subordinate CA Owner" column, or if that's empty, the "CA Owner" column. -

The CCADB's

CAInformationReport, which lists the CAA domains and problem reporting instructions for a subset of CAs. -

For CAs not listed in

CAInformationReport, the information comes from the CA's Certificate Policy (CP) and Certificate Practice Statement (CPS), a pair of documents which describe how the CA is operated. The URL of the applicable CP and CPS can be found inAllCertificateRecords. Section 1.5.2 of the CPS contains problem reporting instructions, and Section 4.2 of either the CP or CPS lists the CAA domains.

In a few cases I've manually curated the data to be more helpful. The most notable example is Amazon Certificate Manager. When you get a certificate through ACM, it's issued by DigiCert from a white-label intermediate certificate with "Amazon" in its name, similar to Cloudflare. However, Amazon has gone several steps further than Cloudflare in white-labeling:

To authorize ACM certificates, you put amazon.com in your CAA record, not digicert.com.

Amazon operates their own root certificates which have signed the white-label intermediates operated by DigiCert. This is highly unusual. Recall that the DigiCert-operated Cloudflare intermediate is signed by a DigiCert-operated root, as is typical for white-label intermediates. (Why does Amazon operate roots whose sole purpose is to cross-sign intermediates operated by another CA? I assume it was to get to market more quickly. I have no clue why they are still doing things this way after 8 years.)

If you look up one of Amazon's intermediates in AllCertificateRecords,

it will say that it is operated by DigiCert. But due to the extreme

level of white-labeling, I think telling users that ACM certificates

were issued by "DigiCert" would cause more confusion than saying they

were issued by "Amazon". So here's what SSLMate's CT Search API returns

for an ACM certificate:

{

"id":"3837618459",

"tbs_sha256":"9c312eef7eb0c9dccc6b310dcd9cf6be767b4c5efeaf7cb0ffb66b774db9ca52",

"cert_sha256":"7e5142891ca365a79aff31c756cc1ac7e5b3a743244d815423da93befb192a2e",

"dns_names":["1.aws-lbr.amazonaws.com","amazonaws-china.com","aws.amazon.com", ...],

"pubkey_sha256":"8c296c2d2421a34cf2a200a7b2134d9dde3449be5a8644224e9325181e9218bd",

"issuer":{

"friendly_name":"Amazon",

"website":"https://www.amazontrust.com/",

"caa_domains":["amazon.com","amazontrust.com","awstrust.com","amazonaws.com","aws.amazon.com"],

"operator":{"name":"DigiCert","website":"https://www.digicert.com/"},

"pubkey_sha256":"252333a8e3abb72393d6499abbacca8604faefa84681ccc3e5531d44cc896450",

"name":"C=US, O=Amazon, OU=Server CA 1B, CN=Amazon"

},

"not_before":"2022-06-13T00:00:00Z",

"not_after":"2023-06-11T23:59:59Z",

"revoked":false,

"problem_reporting":"Send email to revoke@digicert.com or visit https://problemreport.digicert.com/"

}

As you can see, friendly_name and website refer

to Amazon. However, the problem_reporting field

tells you to contact DigiCert, and the operator field makes clear

that the issuer is really operated by DigiCert.

I've overridden a few other cases as well. Whenever a certificate issuer

uses a distinct set of CAA domains, I override the friendly name to match

the domains. My reasoning is that CAA and Certificate Transparency are often

used in conjunction - a site operator might first publish CAA records,

and then monitor Certificate Transparency to detect violations of their

CAA records. Or, they might first use Certificate Transparency to figure

out who their certificate authorities are, and then publish matching CAA records.

Thus, ensuring consistency between CAA and CT provides the best experience.

In fact, the certificate authority names that you see on

SSLMate's CAA Record Helper

are the exact same values you can see in the friendly_name field.

If you're looking for a certificate monitoring solution, consider Cert Spotter, which notifies you when certificates are issued for your domains, or SSLMate's Certificate Transparency Search API, which lets you search Certificate Transparency logs by domain name.

January 10, 2023

whoarethey: Determine Who Can Log In to an SSH Server

Filippo Valsorda has a neat SSH server

that reports the GitHub username of the connecting client. Just SSH to whoami.filippo.io, and if you're

a GitHub user, there's a good chance it will identify you. This works

because of two behaviors: First, GitHub publishes your authorized public

keys at https://github.com/USERNAME.keys. Second,

your SSH client sends the server the public key of every one of your

key pairs.

Let's say you have three key pairs, FOO, BAR, and BAZ.

The SSH public key authentication protocol works like this:

Client: Can I log in with public key

FOO?

Server looks forFOOin ~/.ssh/authorized_keys; finds no match

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAR?

Server looks forBARin ~/.ssh/authorized_keys; finds no match

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAZ?

Server looks forBAZin ~/.ssh/authorized_keys; finds an entry

Server: Yes

Client: OK, here's a signature from private keyBAZto prove I own it

whoami.filippo.io works by taking each public key sent by the client

and looking it up in a map from public key to GitHub username, which Filippo populated

by crawling the GitHub API. If it finds a match, it tells the client the GitHub username:

Client: Can I log in with public key

FOO?

Server looks upFOO, finds no match

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAR?

Server looks upBAR, finds no match

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAZ?

Server looks upBAZ, finds a match to user AGWA

Server: Aha, you're AGWA!

This works the other way as well: if you know that AGWA's public keys

are FOO, BAR, and BAZ, you can send each of them to the server to see if

the server accepts any of them, even if you don't know the private keys:

Client: Can I log in with public key

FOO?

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAR?

Server: No

Client: Can I log in with public keyBAZ?

Server: Yes

Client: Aha, AGWA has an account on this server!

This behavior has several implications:

If you've found a server that you suspect belongs to a particular GitHub user, you can confirm it by downloading their public keys and asking if the server accepts any of them.

If you want to find servers belonging to a particular GitHub user, you could scan the entire IPv4 address space asking each SSH server if it accepts any of the user's keys. This wouldn't work with IPv6, but scanning every IPv4 host is definitely practical, as shown by masscan and zmap.

If you've found a server and want to find out who controls it, you can try asking the server about every GitHub user's keys until it accepts one of them. I'm not sure how practical this would be; testing every GitHub user's keys would require sending an enormous amount of traffic to the server.

As a proof of concept, I've created whoarethey, a small Go program that takes the hostname:port of an SSH server, an SSH username, and a list of GitHub usernames, and prints out the GitHub username which is authorized to connect to the server. For example, you can try it on a test server of mine:

$ whoarethey 172.104.214.125:22 root github:AGWA github:FiloSottile github:AGWA

whoarethey reports that I, but not Filippo, can log into root@172.104.214.125.

You can also use whoarethey with public key files stored locally, in which

case it prints the name of the public key file which is accepted:

Note that just because a server accepts a key (or claims to

accept a key), it doesn't mean that the holder of the private

key authorized the server to accept it. I could take Filippo's public key

and put it in my authorized_keys file, making it look

like Filippo controls my server. Therefore, this information leak doesn't provide

incontrovertible proof of server control.

Nevertheless, I think it's a useful way to deanonymize a server,

and it concerns me much more than whoami.filippo.io.

I only SSH to servers which already know who I am, and

I'm not very worried about being tricked into connecting

to a malicious server - it's not like the Web where it's trivial

to make someone visit a URL.

However,

I do have accounts on a few servers which are not otherwise

linkable to me, and it came as an unpleasant surprise that anyone

would be able to learn that I have an account just by asking the

SSH server.

The simplest way to thwart whoarethey

would be for SSH servers to refuse to answer if a particular public key would be accepted, and instead make clients pick

a private key and send the signature to the server. Although I don't know of any SSH servers that can be configured

to do this, it could be done within the bounds

of the current SSH protocol. The user experience would be the same for people who use a single key per client, which I assume

is the most common configuration. Users with multiple keys would need

to tell their client which key they want to use for each server, or

the client would have to try every key, which might require the user to enter a

passphrase or press a physical button for each attempt.

(Note that to prevent a timing leak, the server should verify the signature

against the public key provided by the client before checking if the

public key is authorized. Otherwise, whoarethey could determine if a public key is authorized by sending an

invalid signature and measuring how long it takes the server to reject it.)

There's a more complicated solution (requiring protocol changes and fancier cryptography) that leverages private set intersection

to thwart both whoarethey and whoami.filippo.io. However, it treats SSH keys as encryption

keys instead of signing keys, so it wouldn't work with hardware-backed keys like the YubiKey. And it requires

the client to access the private key for every key pair, not just the one accepted by the server, so the user experience for

multi-key users would be just as bad as with the simple solution.

Until one of the above solutions is implemented, be careful if you administer any servers which you don't want

linked to you. You could use unique key pairs for such servers, or keep SSH firewalled

off from the Internet and connect over a VPN. If you do use a unique key pair, make sure

your SSH client never tries to send it to other servers - a less benign version of whoami.filippo.io could save

the public keys that it sees, and then feed them to whoarethey to find your servers.

December 12, 2022

No, Google Did Not Hike the Price of a .dev Domain from $12 to $850

It was perfect outrage fodder, quickly gaining hundreds of upvotes on Hacker News:

As you know, domain extensions like .dev and .app are owned by Google. Last year, I bought the http://forum.dev domain for one of our projects. When I tried to renew it this year, I was faced with a renewal price of $850 instead of the normal price of $12.

It's true that most .dev domains are just $12/year. But this person never paid $12 for forum.dev. According to his own screenshots, he paid 4,360 Turkish Lira for the initial registration on December 6, 2021, which was $317 at the time. So yes, the price did go up, but not nearly as much as the above comment implied.

According to a Google worker, this person should have paid the same, higher price in 2021, since forum.dev is a "premium" domain, but got an extremely favorable exchange rate so he ended up paying less. That's unsurprising for a currency which is experiencing rampant inflation.

Nevertheless, domain pricing has become quite confusing in recent years, and when reading the ensuing Hacker News discussion, I learned that a lot of people have some major misconceptions about how domains work. Multiple people said untrue or nonsensical things along the lines of "Google has a monopoly on the .dev domain. GoDaddy doesn't have a monopoly on .com, .biz, .net, etc." So I decided to write this blog post to explain some basic concepts and demystify domain pricing.

Registries vs Registrars

If you want to have an informed opinion about domains, you have to understand the difference between registries and registrars.

Every top-level domain (.com, .biz, .dev, etc.) is controlled by exactly one registry, who is responsible for the administration of the TLD and operation of the TLD's DNS servers. The registry effectively owns the TLD. Some registries are:

| .com | Verisign |

|---|---|

| .biz | GoDaddy |

| .dev |

Registries do not sell domains directly to the public. Instead, registrars broker the transaction between a domain registrant and the appropriate registry. Registrars include Gandi, GoDaddy, Google, Namecheap, and name.com. Companies can be both registries and registrars (Technically, they're required to be separate legal entities; e.g. Google's registry is the wholly-owned subsidiary Charleston Road Registry): e.g. GoDaddy and Google are registrars for many TLDs, but registries for only some TLDs.

When you buy or renew a domain, the bulk of your registration fee goes to the registry, with the registrar adding some markup. Additionally, 18 cents goes to ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers), who is in charge of the entire domain system.

For example, Google's current .com price of $12 is broken down as follows:

| $0.18 | ICANN fee |

|---|---|

| $8.97 | Verisign's registry fee |

| $2.85 | Google's registrar markup |

Registrars typically carry domains from many different TLDs, and TLDs are typically available through multiple registrars. If you don't like your registrar, you can transfer your domain to a different one. This keeps registrar markup low. However, you'll always be stuck with the same registry. If you don't like their pricing, your only recourse is to get a whole new domain with a different TLD, which is not meaningful competition.

At the registry level, it's not true that there is no monopoly on .com - Verisign has just as much of a monopoly on .com as Google has on .dev.

At the registrar level, Google holds no monopoly over .dev - you can buy .dev domains through registrars besides Google, so you can take your business elsewhere if you don't like the Google registrar. Of course, the bulk of your fee will still go to Google, since they're the registry.

ICANN Price Controls

So if .com is just as monopoly-controlled as .dev, why are all .com domains the same low price? Why are there no "premium" domains like with .dev?

It's not because Verisign is scared by the competition, since there is none. It's because Verisign's contract with ICANN is different from Google's contract with ICANN.

The .com registry agreement between Verisign and ICANN capped the price of .com domains at $7.85 in 2020, with at most a 7% increase allowed every year. Verisign has since imposed two 7% price hikes, putting the current price at $8.97.

In contrast, .dev is governed by ICANN's standard registry agreement, which has no price caps. It does, however, forbid "discriminatory" renewal pricing:

In addition, Registry Operator must have uniform pricing for renewals of domain name registrations ("Renewal Pricing"). For the purposes of determining Renewal Pricing, the price for each domain registration renewal must be identical to the price of all other domain name registration renewals in place at the time of such renewal, and such price must take into account universal application of any refunds, rebates, discounts, product tying or other programs in place at the time of renewal. The foregoing requirements of this Section 2.10(c) shall not apply for (i) purposes of determining Renewal Pricing if the registrar has provided Registry Operator with documentation that demonstrates that the applicable registrant expressly agreed in its registration agreement with registrar to higher Renewal Pricing at the time of the initial registration of the domain name following clear and conspicuous disclosure of such Renewal Pricing to such registrant, and (ii) discounted Renewal Pricing pursuant to a Qualified Marketing Program (as defined below). The parties acknowledge that the purpose of this Section 2.10(c) is to prohibit abusive and/or discriminatory Renewal Pricing practices imposed by Registry Operator without the written consent of the applicable registrant at the time of the initial registration of the domain and this Section 2.10(c) will be interpreted broadly to prohibit such practices.

This means that Google is only allowed to increase a domain's renewal price if it also increases the renewal price of all other domains. If Google wants to charge more to renew a "premium" domain, the higher price must be clearly and conspicuously disclosed to the registrant at time of initial registration. This prevents Google from holding domains hostage: they can't set a low price and later increase it after your domain becomes popular.

(By displaying prices in lira instead of USD for forum.dev, did Google violate the "clear and conspicuous" disclosure requirement? I'm not sure, but if I were a registrar I would display prices in the currency charged by the registry to avoid misunderstandings like this.)

I wouldn't assume that the .com price caps will remain forever. .org used to have price caps too, before switching to the standard registry agreement in 2019. But even if .com switched to the standard agreement, we probably wouldn't see "premium" .com domains: at this point, every .com domain which would be considered "premium" has already been registered. And Verisign wouldn't be allowed to increase the renewal price of already-registered domains due to the need for disclosure at the time of initial registration.

There ain't no rules for ccTLDs (.io, .tv, .au, etc.)

It's important to note that registries for country-code TLDs (which is every 2-letter TLD) do not have enforceable registry agreements with ICANN. Instead, they are governed by their respective countries (or similar political entities), which can do as they please. They can sucker you in with a low price and then hold your domain hostage when it gets popular. If you register your domain in a banana republic because you think the TLD looks cool, and el presidente wants your domain to host his cat pictures, tough luck.

This is only scratching the surface of what's wrong with ccTLDs, but that's a topic for another blog post. Suffice to say, I do not recommend using ccTLDs unless all of the following are true:

- You live in the country which owns the ccTLD and don't plan on moving.

- You don't expect the region where you live to secede from the political entity which owns the ccTLD. (Just ask the British citizens who had .eu domains.)

- You trust the operator of the ccTLD to be fair and competent.

Further Complications

To make matters more confusing, sometimes when you buy a domain from a registrar, you're not getting it from the registry, but from an existing owner who is squatting the domain. In this case, you pay a large upfront cost to get the squatter to transfer the domain to you, after which the domain renews at the lower, registry-set price. It used to be fairly obvious when this was happening, as you'd transact directly with the squatter, but now several registrars will broker the transaction for you. The Google registrar calls these "aftermarket" domains, which I think is a good name, but other registrars call them "premium" domains, which is confusing because such domains may or may not be considered "premium" by the registry and subject to higher renewal prices.

Yet another confounding factor is that registrars sometimes steeply discount the initial registration fee, taking a loss in the hope of making it up with renewals and other services.

To sum up, there are multiple scenarios you may face when buying a domain:

| Scenario | Initial Fee | Renewal Fee |

|---|---|---|

| Non-premium domain, no discount | $$ | $$ |

| Non-premium domain, first year discount | $ | $$ |

| Premium domain, no discount | $$$ | $$$ |

| Premium domain, first year discount | $$ | $$$ |

| Aftermarket non-premium domain | $$$$ | $$ |

| Aftermarket premium domain | $$$$ | $$$ |

| ccTLD domain | Varies | Sky's the limit! |

I was curious how different registrars distinguish between these cases, so I tried searching for the following domains at Gandi, GoDaddy, Google, Namecheap, and name.com:

- safkjfkjfkjfdkjdfkj.com and nonpremium.online - decidedly non-premium domains

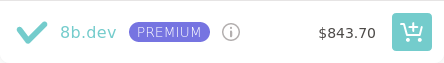

- 8b.dev - premium domain

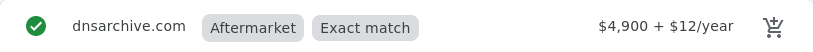

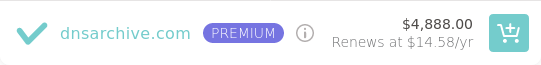

- dnsarchive.com - aftermarket domain

Gandi

Non-premium domain, no discount:

Non-premium domain, first year discount:

Premium domain:

Gandi does not seem to sell aftermarket domains.

GoDaddy

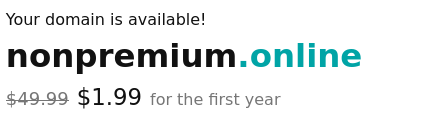

Non-premium domain, first year discount:

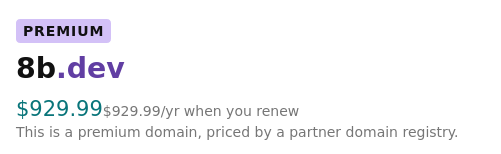

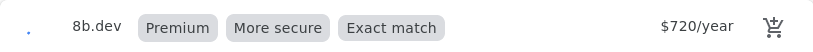

Premium domain:

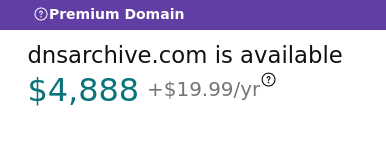

Aftermarket domain:

Non-premium domain, no discount:

Premium domain:

Aftermarket domain:

Namecheap

Non-premium domain, first year discount:

Premium domain:

Aftermarket domain:

name.com

Non-premium domain, first year discount:

Premium domain:

Aftermarket domain:

Thoughts

I think Gandi and Google do the best job conveying the first year and renewal prices using clear and consistent UI. Unfortunately, since the publication of this post, Gandi has been acquired by another company, and Google is discontinuing their registrar service. Namecheap is the worst, only showing a clear renewal price when it's less than the initial price, but obscuring it when it's the same or higher (note the use of the term "Retail" instead of "Renews at", and the lack of a "/yr" suffix for the 8b.dev price). name.com also obscures the renewal price for nonpremium.online (I very much doubt it's $1.99). GoDaddy also fails to show a clear renewal price for the non-premium domains, but at least says the quoted price is "for the first year."

My advice is to pay very close attention to the renewal price when buying a domain, because it may be the same, lower, or higher than the first year's fee. And be very wary of 2-letter TLDs (ccTLDs).